Jud, A., & Trocmé, N. (2012). Physical Abuse and Physical Punishment in Canada. Child Canadian Welfare Research Portal Information Sheet # 122E.

The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2008 (CIS-2008) is the third nation-wide study to examine the incidence of reported child maltreatment and the characteristics of children and families investigated by child welfare authorities in Canada. In addition to the tables presented in the Major Finding report (Trocmé, Fallon, MacLaurin et al. 2010), this Information Sheet describes rates of specific forms of substantiated physical abuse, physical harm and physical punishment.

Substantiated forms of physical abuse

An estimated 18,688 cases of physical abuse were substantiated in Canada in 2008, a rate of 3.1 cases of substantiated physical abuse per 1,000 children. In most of these cases (17,212) physical abuse was the primary form of maltreatment; in 1,476 cases, physical abuse was a secondary form. Cases were classified as physical abuse if the child had been physically harmed or was at substantial risk of suffering physical harm, as a result of one of the five following abusive acts:

- Shake, push, grab, or throw: includes pulling or dragging a child as well as shaking an infant

- Hit with hand: includes slapping and spanking but not punching

- Punch, kick, or bite: includes any hitting with other parts of the body (e.g., elbow or head)

- Hit with object: includes hitting with a stick, a belt, or other object, throwing an object at a child, but not stabbing with a knife

- Other physical abuse: any other form of physical abuse including choking, strangling, stabbing, burning, shooting, poisoning, and the abusive use of restraints.

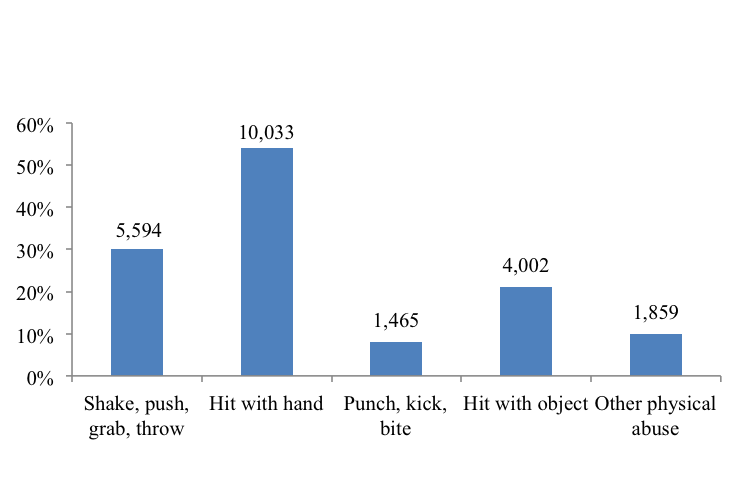

As shown in Figure 1, just over half (54%) of the substantiated physical abuse cases involved a child being hit with a hand. An estimated 30% of cases involved a child being shaken, pushed, grabbed, or thrown, 21% involved a child being hit with an object, 8% being punched, kicked, or bitten and 10% of physical abuse cases were classified as involving “other” physical abuse. Because substantiated physical abuse cases can involve more than one form of abuse, the five forms described in Figure 1 add up to more than 100%.

Figure 1: Forms of Substantiated Physical Abuse, CIS-2008

Physical harm1

Investigating workers were asked to document the nature of physical harm caused by the substantiated maltreatment. These ratings are based on the information routinely collected during a maltreatment investigation. While investigation protocols require careful examination of any physical injuries and may include a medical examination, it should be noted that children are not necessarily examined by a medical practitioner. Types of injury or health conditions that were documented include:

- No harm: there was no apparent evidence of physical harm to the child as a result of maltreatment

- Bruises/cuts/scrapes: the child suffered various physical injuries visible for at least 48 hours

- Broken bones: the child suffered fractured bones

- Head trauma: the child was a victim of head trauma, including internal brain injuries due to shaking

- Other health conditions: the child suffered from other physical health conditions, such as complications from untreated asthma, failure to thrive, or a sexually transmitted disease.

As shown in Table 1, no physical harm was documented in approximately three-quarters of cases of substantiated physical abuse reported in the CIS-2008 (13,639 cases). For the 4,672 cases that included documentation of physical harm, most involved bruises, cuts, and scrapes (4,133, 88%); more severe injuries such as broken bones and head trauma were rarely indicated.

Table 1: Physical Harm Noted in Cases of Substantiated Physical Abuse, CIS-2008

| Estimate | Proportion | |

|---|---|---|

| No documented physical harm | 13,639 | 74% |

| Documented physical harm | 4,672 | 26% |

| Forms of physical harm: | ||

| Bruises/cuts/scrapes | 4,133 | 23% |

| Broken bones | 110 | 1% |

| Head trauma | 308 | 2% |

| Other health condition | 325 | 2% |

| Substantiated physical abuse1,2 | 18,311 | 100% |

1: Excludes physical abuse causes where harm was attributed to failure to supervise

2: Because more than one form of harm can be noted, rows add up to more than total

Severity of harm

Medical treatment was required in an estimated 6% (979) of child investigations where physical abuse was the primary form of substantiated maltreatment. During the three-month CIS-2008 case selection period there were two substantiated investigations of a child fatality. Because these tragic events occur relatively rarely, estimates of the rate of child fatalities cannot be derived.

Abusive physical punishment

Nearly three quarters (74%) of all cases of substantiated physical abuse were considered by the investigating worker to have occurred in a context of punishment, an estimated rate of 2.3 cases of substantiated punitive physical abuse per 1,000 children in Canada. While punishment was rarely (6%) noted as a factor in most other cases of substantiated maltreatment, 27% of substantiated emotional maltreatment incidents were also considered to have been initiated as a form punishment.

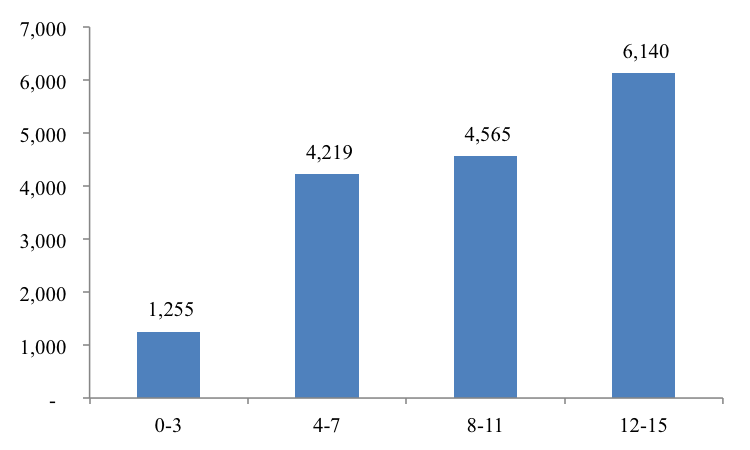

An estimated 16,179 cases of punitive violence, which includes all forms of maltreatment arising as a result of punishment, were substantiated in Canada in 2008. As shown in Figure 2, the use of punitive violence increases with age, ranging from an estimated 1,255 substantiated cases of punitive violence involving children under 4 to 6,140 involving youth between the ages of 12 to 15.

For information about the effects of physical punishment on the development of children please see Durrant and Ensom's (2012) review in the Canadian Medical Association's Journal (http://www.cmaj.ca/content/184/12/1373).

Figure 2: Substantiated Punitive Violence by Age, CIS-2008

Background to the CIS-2008

Responsibility for protecting and supporting children at risk of abuse and neglect falls under the jurisdiction of the 13 Canadian provinces and territories and a system of Aboriginal child welfare agencies which have increasing responsibility for protecting and supporting Aboriginal children. Because of variations in the types of situations that each jurisdiction includes under its child welfare mandate as well as differences in the way service statistics are kept, it is difficult to obtain a nation-wide profile of the children and families receiving child welfare services. The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) is designed to provide such a profile by collecting information on a periodic basis from every jurisdiction using a standardized set of definitions. With core funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada and in-kind and financial support from a consortium of federal, provincial, territorial, Aboriginal and academic stakeholders, the CIS-2008 is the third nation-wide study of the incidence and characteristics of investigated child abuse and neglect across Canada.

Methodology

The CIS-2008 used a multi-stage sampling design to select a representative sample of 112 child welfare service agencies in Canada and then to select a sample of cases within these agencies. Information was collected directly from child protection workers on a representative sample of 15,980 child protection investigations conducted during a three-month sampling period in the fall of 2008. This sample was weighted to reflect provincial annual estimates.

For maltreatment investigations, information was collected regarding the primary form of maltreatment investigated as well as the level of substantiation for that maltreatment. Thirty-two forms of maltreatment were listed on the data collection instrument, and these were collapsed into five broad categories: physical abuse (e.g., hit with hand), sexual abuse (e.g., exploitation), neglect (e.g., educational neglect), emotional maltreatment (e.g., verbal abuse or belittling), and exposure to intimate partner violence (e.g., direct witness to physical violence). Workers listed the primary concern for the investigation, and could also list secondary and tertiary concerns.

For each form of maltreatment listed, workers assigned a level of substantiation. Maltreatment could be substantiated (i.e., the balance of evidence indicated that an incident of maltreatment had occurred), suspected (i.e., maltreatment could not be confirmed nor ruled out) or unfounded (i.e., the balance of evidence indicated that an incident of maltreatment had not occurred).

For each risk investigation, workers determined whether the child was at risk of future maltreatment. The worker could decide that the child was at risk of future maltreatment (confirmed risk), that the child was not at risk of future maltreatment (unfounded risk), or that the future risk of maltreatment was unknown.

A detailed presentation of the study methodology and of the definitions of each variable is available at http://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/en/CIS_2008_Methods_March_2013.pdf

Limitations of the CIS-2008

The CIS collects information directly child welfare workers at the point when they completed their initial investigation of a report of possible child abuse or neglect, or risk of future maltreatment. Therefore, the scope of the study is limited to the type of information available to them at that point. The CIS does not include information about unreported maltreatment nor about cases that were investigated only by the police. Also, reports that were made to child welfare authorities but were screened out (not opened for investigation) were not included. Similarly, reports on cases currently open at the time of case selection were not included. The study did not track longer-term service events that occurred beyond the initial investigation.

Three limitations to estimation method used to derive annual estimated should also be noted. The agency size correction uses child population as a proxy for agency size; this does not account for variations in per capita investigation rates across agencies in the same strata. The annualization weight corrects for seasonal fluctuation in the volume of investigations, but it does not correct for seasonal variations in types of investigations conducted. Finally, the annualization weight includes cases that were investigated more than once in the year as a result of the case being re-opened following a first investigation completed earlier in the same year. Accordingly, the weighted annual estimates represent the child maltreatment-related investigations, rather than investigated children.

Comparisons across CIS reports must be made with caution. The forms of maltreatment tracked by each cycle were modified to take into account changes in investigation mandates and practices. Comparisons across cycles must in particular take into consideration the fact that the CIS-2008 was the first to explicitly track risk-only investigations. In addition, readers are cautioned to avoid making direct comparisons with provincial and First Nations oversampling report because of differences in the way national and oversampling estimates are derived.

References:

Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Sinha, V., Black, T., Fast, E., Felstiner, C., Hélie, S., Turcotte, D., Weightman, P., Douglas, J., & Holroyd, J., (2010) Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect – 2008: Executive Summary & Chapters 1-5. Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, 2010. http://cwrp.ca/publications/2117

Durrant, J & Ensom, R. (2012) Physical punishment of children: lessons from 20 years of research. CMAJ 184 (12) http://www.cmaj.ca/content/184/12/1373

[1] Cases with “failure to supervise: physical harm” as the primary form of substantiated maltreatment were excluded, representing an estimated 377 cases where physical abuse was a secondary form of substantiated maltreatment (N=29).